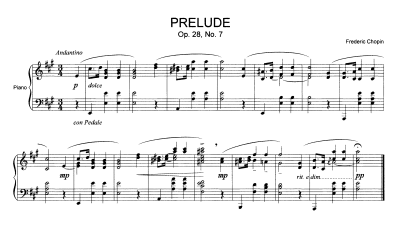

Almost everyone who plays the piano has, at some point in his/her study, learned Chopin’s Prelude in A Major, Op. 28. Only 16 bars and lasting a bit less to a bit more than a minute (depending on the performer), the Prelude is deceptively simple. A few repetitions and it feels as though we have it “under our fingers;” a few more repetitions and hey! we’ve memorized it!

Almost everyone who plays the piano has, at some point in his/her study, learned Chopin’s Prelude in A Major, Op. 28. Only 16 bars and lasting a bit less to a bit more than a minute (depending on the performer), the Prelude is deceptively simple. A few repetitions and it feels as though we have it “under our fingers;” a few more repetitions and hey! we’ve memorized it!

But wait – leave it for a couple of days, and all of a sudden, you begin to wonder: which bars in the left hand had an open octave, which had a fifth, which had chord inversions? Is the right hand exactly the same when it repeats in bar 9 as it is in the first bar or has something changed? Is the chord in the left hand always the same on the 2nd and 3rd beats of the odd-numbered measures?

As long as we keep repeating the Prelude during a practice session (massed practice), we are using short-term or working memory. And because the piece continues to improve, we feel as though we have really made progress. But the results won’t last, which is why we aren’t certain about notes or harmonies a couple of days later. We need to find ways of practicing that facilitate the transfer to long-term memory, so here are some suggestions based on what cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists have discovered about learning and memory :

1) Spaced or distributed practice has been known about by psychologists for more than a hundred years, but somehow, it isn’t taught in most schools – or taught by most music teachers. But research on distributed practice shows that learning is retained much longer when our practice or study is distributed over time rather than when it is concentrated.

OK, musicians certainly distribute our practice over time (unless we are cramming for an unexpected performance or for a jury). We learn a piece over a period of days, weeks, or months. There is always time between practice sessions. But what researchers are talking about is spacing within a practice session when you are initially learning the piece. They say that continuing to repeat a new excerpt of music after you have just learned it is not as effective as leaving it and practicing it again later during your practice session – maybe 20 minutes later if the piece is new, maybe an hour, adding longer intervals as the piece becomes more familiar – eventually spacing by a day or two, and longer.

Why is this the case? Well, there’s some debate about that, but researchers believe that all of the following information that they have discovered about the brain may apply:

a) The brain likes novelty and it pays attention to what’s new. The more you repeat an excerpt of music, the less novelty it has for the brain, so the brain stops paying attention, which means all of those repetitions really aren’t doing any good. What distributed practice suggests is that you practice the excerpt, but maybe for a shorter period of time. When you come back to it an hour or two later, the excerpt will seem new compared to what you have been practicing – or doing – in the interim, and the brain will again pay attention.

b) Spaced or distributed practice adds different contextual cues. Contextual cues may be subconscious, but are encoded in our brain along with the information we are learning so are valuable in terms of recall. Studies have shown that if you study with certain music, you will recall the information more readily if you hear that same music during recall. If you practice all the time in the same practice room, you remember the piece better in that practice room. But obviously, that learning strategy is a bit limited – we can’t take tests with our favorite music playing, and we can’t perform in the practice room. So we want to add as many contextual cues as possible.

The first time you are practicing the Chopin Prelude discussed above, it may be early in the morning. You’re sipping coffee as you practice. It’s extremely quiet in your building or neighborhood. A lot of light is coming through the large window to your left. When you practice the Prelude again later in the day, traffic noise has increased, there is far less light in the room, someone is cooking something wonderful and delicious smells are wafting through the window to your left. Different contextual cues are now added to the encoding of the musical material, which makes your memory stronger. (More on contextual cues in the next post.)

c) Distributed practice makes the brain work harder – it takes more effort to recall the Prelude after an hour than to recall it after you just played it 30 seconds ago. You have to think about which L.H. chords in the Prelude are octaves and which are fifths or how the R.H. is different when the melody repeats. And as I wrote in the previous post, learning lasts longer when it requires more effort. You find out more about what you don’t know with increasingly longer spaces between practice sessions on a particular excerpt or piece, and as you review information, it forces the brain to consolidate the initial memory traces or neural pathways and strengthen them, fill in blank spots, and make synapses stronger.

2) “Mix it up,” or random practice has also been found to be far more effective than massed or repetitive practice, both for motor skills and for cognitive tasks. Mixing up the kinds of music you are practicing or the different technical or musical problems forces the brain to discriminate about the solutions and solidify the neural pathways for each, contributing to better long-term learning.

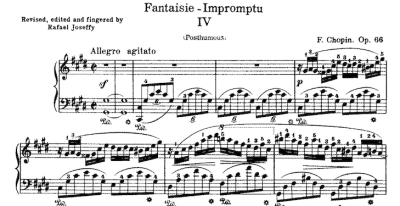

For example, if you are working on the first section of Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu – really struggling with playing the 4 sixteenths in the right hand against three eighths in the left, and you are planning to spend your hour of practice time today really nailing those difficult

polyrhythms – don’t. Practice them for a while and then go on to something totally different – and not the middle section of the piece with its 2:3 polyrhythms – that’s the same kind of rhythmic problem.

Work on something that presents a different kind of technical or musical challenge – perhaps the voicing in a Bach or Hindemith Fugue, or articulation in a Scarlatti Sonata. Random practice is a kind of distributed practice except that you are practicing another piece during the “space.” With distributed practice, the space might be a coffee break or lunch.

Most of us work on several pieces at once and switch from one to another. But how often do we practice a piece from beginning to end each time we practice it, or practice several pieces in the same order each day? The “mix it up” or random strategy suggests that we practice the pieces in a different order each day, that we practice sections of a piece in a different order, that we practice sections of one piece interspersed with sections from another – always varying our practice routine.

This forces the brain to consolidate the different kinds of learning associated with each technical challenge or section of a piece, and it also helps us encode retrieval cues – that information about structure, chord progressions, key relationships, differences in sections, etc., etc., etc., that is crucial to retrieving conceptual memory of a piece as fast as we are playing it. (See previous post)

3) Practice retrieving the piece from long-term memory. Too often, we don’t test our memory until we are close to performance. Instead, try playing from memory almost as soon as you begin learning the piece – a segment here, another section there. Try it from memory for yourself, for friends, for a teacher. It doesn’t matter if you make mistakes. That actually helps you in the learning process – as long as you think about and fix the mistakes – because your brain is forced to make distinctions between what’s right and what’s wrong, and the correct information becomes encoded more strongly.

We are so accustomed to trying to make certain that a piece is solid before trying it from memory that practicing memory retrieval early in the learning process will not feel at all comfortable. But remember that learning is stronger when it requires more effort. The harder we have to work during our initial attempts to play from memory, the more we learn about what we don’t know, and the stronger the neural circuits in the brain will become as the information is consolidated.

We need to practice retrieval of conceptual (declarative) memory just as we practice our motor skills. It isn’t motor skills we lose when we have a memory slip because obviously we would be playing just fine if the score were in front of us. And it usually isn’t auditory memory that we lose either. It’s our conceptual memory that disappears when we have a memory slip. We can’t remember a particular chord, or fingering, or harmonic progression, and it throws us off so that the motor sequence is interrupted. We need to practice retrieving all of those factual cues about the piece so that when a slip does happen, we have ready access to conceptual memory, we know instantly where we are, and we can restart the motor program as quickly as possible.

4) Don’t concentrate only on the learning style that is most comfortable for you. The idea of learning styles has been around for a long time, and learning style theory suggests that we all process new information differently – some of us learning better from visual materials, some from auditory, and some from kinesthetic. As learning styles theory has increasingly been adopted by educational institutions, the idea that we learn best when instruction or study is matched to our learning style has gained traction.

But the research simply isn’t there to conclude the validity of matching learning styles to our practice or study routines. What is clear is that our fallback position is the learning style that is the most comfortable for us. Mine is auditory, and how a piece sounds is always what I learn first.

But when we concentrate on learning styles that come less naturally to us, we add neural connections in the brain that reinforce learning. Again, it is practice or learning that requires effort. Hearing the piece in my mind doesn’t require any effort for me. It just happens. But if I concentrate on “seeing” particular chord changes, “seeing” how the sections are laid out, visualizing how complex chords look on the keyboard, or creating some kind of visual map for myself (see The Memory Map for Music), I will have to work much harder, but all of that visual information adds to the encoding for that particular piece in my brain.

And if I practice motor imagery so that I am thinking about how a particular passage of music “feels” in my muscles, and what kind of movements I must make to play a problematic section, then kinesthetic and proprioceptive information is being encoded. And certainly the memory for a piece will be much stronger if auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and proprioceptive information are all encoded along with the motor information. (More on motor imagery in the following post.)

These methods of practicing are much more difficult than simply repeating something over and over. But your long-term memory will be stronger because you are forcing your brain to work in a variety of ways – to make distinctions, to add neural circuitry for multiple ways of encoding musical information, and to make those neural pathways stronger.

There are two recent books on learning and memory that I highly recommend: Make it Stick: The Science of Successful Learning by Peter Brown, Henry Roediger III, and Mark McDaniel; and How We Learn: The Surprising Truth About When, Where, and Why It Happens, by Benedict Carey.

Neither one is about music. But they both look at recent discoveries in cognitive psychology and other disciplines to show how much of what we think we know about learning is wrong, and they give us techniques for more productive learning and memory that are applicable not only to learning in general, but also to learning music.

More practice strategies next time.

3 responses to “Practice, learning and memory, part II”

I guess there are benefits for those of us who don’t have gobs of practice time! One strategy I use and recommend to my students is to make a copy of the score I’m learning, cut it into pieces, and place the pieces into an envelope. I reach in and grab a section, then work from there. It give me lots of starting places in the piece and helps remind me of changes in the harmonic structure.

Great idea, Kay! Thanks for sharing!

I’m very new to this site, and excited to find great articles combining piano study and cognitive/neuro psych issues. About a year ago, I returned to serious piano study after many years of benign neglect (I’m now retired).

Your discussion about the value of contextual cues reminds me of a problem that is actually the opposite, for me. I find that when I am playing a work from memory that I learned in college (or perhaps earlier), that the act of playing will invariably trigger the recollection of another piece that I studied during that same era in my life. It is quite disconcerting to be (hopefully) concentrating on the work at hand, focusing on being totally “in the moment,”– only to have thoughts flash across my brain such as “oh, play this one next, remember that one, etc.” To become distracted by thinking, albeit briefly, about another piece(s) of music that seems to share neural pathways, somehow linked by time and history, with the piece I’m actually playing– is very challenging to say the least! I cannot consciously list which piece triggers which memory: it is only when the physical muscle movements actually occur. Oddly, I do not experience this if I play from the score; it is only from memory. It is always confined to a specific cluster of material (pieces learned before age 25). Happily, I do not experience it at all with new repertoire (less than 2 years).

I am curious if anyone else experiences this phenomenon, or maybe it’s just me!