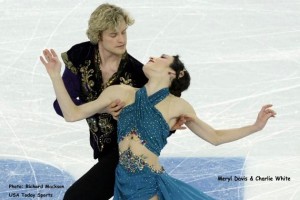

A few years ago, a composer who was writing a piece for me commented at one of our rehearsals that he wanted the audience to breathe the same collective “Aah!” at the end of the work as they do when a figure skater lands a flawless triple axel. We were in the middle of the Olympics at the time, and as we were both fans of figure skating, triple axels were on our minds. We are currently in the middle of another Olympic season and figure skating is again on my mind as I sit mesmerized watching the men’s, women’s, pairs, and ice dancing events. And again I am pondering triple axels and playing the piano. (And yes, I know that the photo at the left does not show a triple axel, but she is such an extraordinary skater!)

A few years ago, a composer who was writing a piece for me commented at one of our rehearsals that he wanted the audience to breathe the same collective “Aah!” at the end of the work as they do when a figure skater lands a flawless triple axel. We were in the middle of the Olympics at the time, and as we were both fans of figure skating, triple axels were on our minds. We are currently in the middle of another Olympic season and figure skating is again on my mind as I sit mesmerized watching the men’s, women’s, pairs, and ice dancing events. And again I am pondering triple axels and playing the piano. (And yes, I know that the photo at the left does not show a triple axel, but she is such an extraordinary skater!)

In the small town in which I grew up, my family lived next door to two outdoor ice rinks, one for hockey and one for free skating. We put our skates on in the kitchen and headed out the door, my brothers to the hockey rink, my sisters and I to the free skate rink. But the last time I skated, at some point in my twenties when I was home on a visit, I found myself on the end of a “crack the whip,” and as we spun around the ice faster and faster, I hit a crack in the ice and went down hard. I had the air knocked out of me, had to be carried home, and haven’t been on skates since.

I thought of that incident as I have been watching the various figure skating competitions. Occasionally someone falls hard, but even as she does, she is picking herself up and moving back into the routine. Which is what an expert does – prepare for the unexpected and know how to deal with it. By the time one is skating in the Olympics, a skater  has practiced tens of thousands of hours, participated in dozens or hundreds of competitions, and had plenty of experience with all kinds of falls. But I was no expert at skating, and that fall unnerved me enough to not do it again.

has practiced tens of thousands of hours, participated in dozens or hundreds of competitions, and had plenty of experience with all kinds of falls. But I was no expert at skating, and that fall unnerved me enough to not do it again.

On the other hand, I’ve had the equivalent of numerous “falls” while performing publicly as a pianist and I do exactly what those skaters do – get myself out of it and go on as though nothing has happened. And in fact, sometimes the audience doesn’t realize that anything has happened. Mistakes at the keyboard are rarely as obvious as mistakes on the ice – and never as potentially dangerous (although I could have ended up on the floor the time that someone neglected to lock the wheels on the piano and it began moving away from me as I was playing).

Obviously, I had the motivation to put in the thousands of hours necessary to achieve a professional level of piano performance but not to achieve a professional level of skating. So what about those thousands of hours?

You’ve all heard about the idea that it takes 10,000 hours or ten years of practice to achieve expert performance in any field, including music and chess. Best-selling author Malcolm Gladwell popularized the idea in his 2008 book Outliers: The Story of Success, writing that “researchers have settled on what they believe is the magic number for true expertise: ten thousand hours.” (p. 40) Or “Ten thousand hours is the magic number of greatness.” (p. 41) Although Gladwell is usually credited with the idea, it wasn’t his – nor did any researcher ever say there was a “magic number” of hours to achieve expertise.

The original research was done in 1993 by K. Anders Ericsson (at that time at the University of Colorado at Boulder, now at Florida State) and two colleagues at the Max Planck Institute in Berlin. The study involved violin students at the Music Academy of West Berlin and professional violinists from the Berlin Philharmonic and the Radio Symphony Orchestra. Music professors at the Academy nominated 14 students with the potential to become international soloists (10 were chosen), another ten students were selected who were good violinists and another ten violinists, who were not intending to be performers, were selected from the music education department.

All of the participants, students and professional, were interviewed about age of beginning study, number of hours of deliberate practice per week, number of hours spent in other musical activities, participation in competitions, etc. Ericsson found that by the age of 20, the students nominated as the “best” violinists had accumulated an average of 10,000 hours of deliberate practice, compared to an average of 7500 for the good violinists, 5000 for the others. The amount of practice accumulated by age 18 by the best student violinists was the same as that of the professional violinists. The study was repeated shortly thereafter with pianists, with similar results.

Ericsson denied that innate talent played any role in the differences between exceptional and average performers. With the exception of a genetic difference, such as height, that may make a difference in some fields, he argued that differences between expert and non-expert performers were due to deliberate practice. He defined deliberate practice as breaking down the skills necessary to become an expert, having the motivation to attend to those skill chunks during practice, repetition of those skill chunks – with ever increasing difficulty, and getting (and paying attention to) immediate feedback from a coach.

Gladwell picked up on the 10,000 hours idea, but didn’t include the “deliberate practice” component, instead adding the idea that no one reaches that “magic number” of 10,000 hours by himself. You have to have supportive parents who have money to support your passion – to hire coaches, teachers, pay for special programs, etc. While Gladwell initially enjoyed a lot of positive acclaim for Outliers, considerable backlash has picked up steam in the past couple of years.

David Epstein from Sports Illustrated has written The Sports Gene: Inside the Science of Extraordinary Athletic Performance, in which he totally debunks Gladwell’s theory, pointing out that there are factors involved in success other than practice. Epstein asks what about the fact that tall players are more likely to make it to the NBA? Or that Jamaicans dominate sprinting? He says he actually wrote the book as a challenge to Gladwell. Daniel Goleman takes on Gladwell in his new book Focus: The Hidden Driver of Excellence, pointing out that if you are a duffer at golf, you can practice the same mistakes for 10,000 hours and still not be any better. (Ericsson would agree, as would any music teacher who hears the same mistakes in the same pieces week after week.)

Meanwhile, on the academic side of things, Ericsson has also received his share of criticism. David Hambrick, a psychologist at Michigan State University and several colleagues from other institutions, analyzed data from multiple studies of top chess players and musicians (yes – musicians and chess players seem to be the two most studied groups concerning “expert performance”). They found, and you will appreciate if I don’t go into a lengthy explanation, that for musicians, only 30% of the variance in their ranks could be chalked up to amount of time practicing, and for chess players, it was 34%. They suggest other possible factors in achieving music expertise, such as starting age, intelligence, personality (as it relates to “passion” for practice), and genes. (Hambrick, D.Z., et al., Deliberate practice: Is that all it takes to become an expert? Intelligence (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2013.04.001)

So what about this “10,000 hours idea” from the performer’s point of view? We don’t have the adage “practice makes perfect” for nothing. We know that becoming a top-level performer on any musical instrument is dependent on thousands or tens of thousands of hours of practice – whether or not this is 30% or 60% of our success, who knows. But there are no shortcuts. We also know that the kind of practice matters – how attentive one is to details, how focused, how analytical. We know that the quality of teachers matters, as does the opportunity to go to good schools, festivals, competitions. Intelligence matters. Being able to analyze a score to understand the composer’s intentions will mean a better performance. And understanding anatomy definitely matters. If you don’t know how your body works, it’s difficult to remain injury-free during all those hours of practice at your instrument or with your voice. But I’m equally certain that many of us can also think of a student or two or three who had the support of parents, who practiced diligently for hours a day, who was extremely intelligent, but who didn’t have the ability to emotionally connect with the music or to communicate the emotion to others. All the practice in the world doesn’t change that.

Could I have been an even moderately good figure skater? I doubt it – no matter how many thousands of hours I practiced. Rather than subscribe to the “10,000 hours creates all experts” theory of expertise, I gravitate more towards Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences proposed in Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences in 1983. Gardner challenged the idea that intelligence is a single capacity that we each have to a greater or lesser degree and instead proposed seven intelligences (linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, intrapersonal, and interpersonal), added an eighth (naturalist) and has considered two others (existential and pedagogical).

While Gardner’s theory proposes that each of us has strengths in one or two of these areas of intelligence, he says that it is the unique combination of these intelligences that each of us has that is the key to our own cognitive profile. Our unique combination of intelligences is also key to becoming an “expert” in one field or another. If you practice the 10,000 hours in an area in which you have strengths, the chances are much greater that you will become an expert at the activity than if you practice in an area in which you don’t have any particular strengths. While I have what Gardner would describe as musical intelligence, I clearly don’t have the spatial or bodily-kinesthetic intelligence that would have allowed me – whether with 10,000 hours or even 20,000 hours – to become an expert at figure skating – or dancing, for that matter. Maybe in my next life!

2 responses to “Triple axels and the piano”

Delighted to see the reference to the Gardner book. I got the hardback when it first came out and the ideas in it really helped me in my work as a music therapist. I pushed them even further with the notion that there are frames of mind within the subset of musical intelligence – some people get some aspects of music making, e.g. rhythm or harmony or being a performer, better than other aspects. Finding each person’s strength and then working out from that seems to be the way to go.

Recently I’ve seen people saying Gardner’s ideas aren’t fully backed up by the new research – and that may well be the case – but the concepts are very handy tools until something else comes along.

(Also, enjoyed your comment over on Kyle Gann’s blog regarding academic jargon)

Hi Lyle, You’re right about people having different strengths within the musical intelligence framework. I’ve seen ample evidence of that from teaching piano for so many years. And certainly performers and composers both have musical intelligence but exhibit it in different ways – and of course, whatever other blend of intelligences someone has plays into that as well. I know there is increasing criticism of the MI theory – probably because it works so well. Some of that comes from the testing community – not wanting anything other than what is tested by IQ to be called “intelligence.” But one only has to look at Picasso, who barely made it through elementary school – had trouble learning to read and write and had lots of trouble learning numbers. On any basic IQ test, he would have scored extremely low, but no one can say he didn’t have intelligence in visual-spatial areas. I think to call that kind of intelligence merely a “talent” is to denigrate it and make it less consequential than verbal and mathematical abilities that are rated on IQ tests. Precisely what Gardner was trying to avoid.