What if practicing the piano (or another instrument) helped your brain to remain healthy longer in life? Well, in fact, it may do exactly that. Some of the most exciting brain and music research in the past few years shows that older adults who have never had any music lessons show neuroplastic changes in areas of the brain having to do with cognition with just one year of practicing and listening to music.

Neuroplasticity is the brain’s ability to change or reorganize itself in response to experience, learning new things, or recovering from injury. It does this by forming new neural connections, strengthening existing connections, and sometimes shifting function from one area to another, such as when the visual cortex in a blind person is repurposed to process signals from hearing or touch.

Neuroscientists used to believe that the brain was “hardwired” by the teenage years and change was no longer possible, but they now know that the brain continues to be neuroplastic throughout life. Neuroplasticity does not happen as quickly as we get older, and at a certain point, it begins to decrease and the brain eventually starts to atrophy. Cognitive decline begins to appear. But that is not always inevitable or irreversible.

In early September, I published the first post in a series of articles that will introduce new research demonstrating that piano lessons, even begun late in life, lead to healthy aging and can delay dementia. If you haven’t read “Might music making be a fountain of youth?” you may want to do so before continuing. But a short recap: Because making music uses so many areas of the brain, neuroscientists say that “making music is the most complex cognitive activity in which a human can engage.” Because of that, we build cognitive reserve when we learn and continue to play a musical instrument, and cognitive reserve delays aging. (Cognitive reserve is discussed in greater detail in the above-linked post.)

Some of the cognitive functions that decline during the normal aging process are 1) executive functions, 2) processing speed, 3) the ability to hear speech in noise, and 4) visuospatial abilities. But those functions don’t decline to the same extent in musicians. Several studies comparing older musicians to non-musicians have shown that musicians are stronger in all of these areas of cognition, and that means that musicians have greater cognitive reserve, thus reducing the risk of dementia.

In this post, we’re going to look at the brain areas that are necessary for making music, how we build cognitive reserve in those areas when we learn and practice a musical instrument, and how that cognitive reserve delays the decline of the cognitive functions listed above.

Areas of the brain necessary for making music

Each labelled area in the image at the left is involved when we make music. The prefrontal cortex, shown at the left on the top image, is where thinking, planning, working memory, and attention are processed. The premotor cortex and supplementary motor cortex are responsible for the planning, preparation, and guidance of the motor movements we need to make to play our instrument. The motor cortex sends signals to our muscles to initiate those movements. The somatosensory cortex is responsible for processing sensory information and touch; the superior parietal lobe translates spatial information from a score into complicated motor commands. The visual cortex processes vision, the auditory cortex processes hearing, and the cerebellum coordinates motor activity and is involved in timing.

Moving to the lower of the two images, the corpus callosum is a mass of nerve fibers that connects the two hemispheres of the brain. Since the left hemisphere controls the right side of the body and the right hemisphere controls the left and all instrumentalists use both hands (and sometimes feet), a great deal of information travels back and forth via the corpus callosum. The basal ganglia automates skilled movements and stores movement programs. One neuroscientist has referred to it as a kind of zip file. Your brain doesn’t have to figure out each individual motor movement in a piece each time you play it. The basal ganglia “stitches” them together and stores them in patterns or groups. The hippocampus processes memory and the amygdala processes emotion, both of which are crucial when we make music. You don’t need to remember what all of these brain areas are, but just think about the vast amount of brain “real estate” that is involved in music making.

Neurons form pathways and networks within the brain that connect all of these areas necessary for music. We know that, as we practice, our skill increases and we are not only able to play faster but to play increasingly difficult music. What makes that possible is that, in the brain, more neurons are being added to the network, the synapses (connections between neurons) become stronger, and transmission becomes faster. The brain changes and that is called neuroplasticity.

We see those changes in terms of improved technique and musicianship, but as these brain areas necessary for music are being repeatedly used, the brain is building cognitive reserve. And that cognitive reserve extends beyond making music to other areas of our lives as well.

Building cognitive reserve

Let’s look at the four areas of cognitive function mentioned above that decline during the aging process and see how making music strengthens each of those areas. (A more complete discussion of the cognitive functions below as they pertain to music can be found in my book, The Musical Brain.)

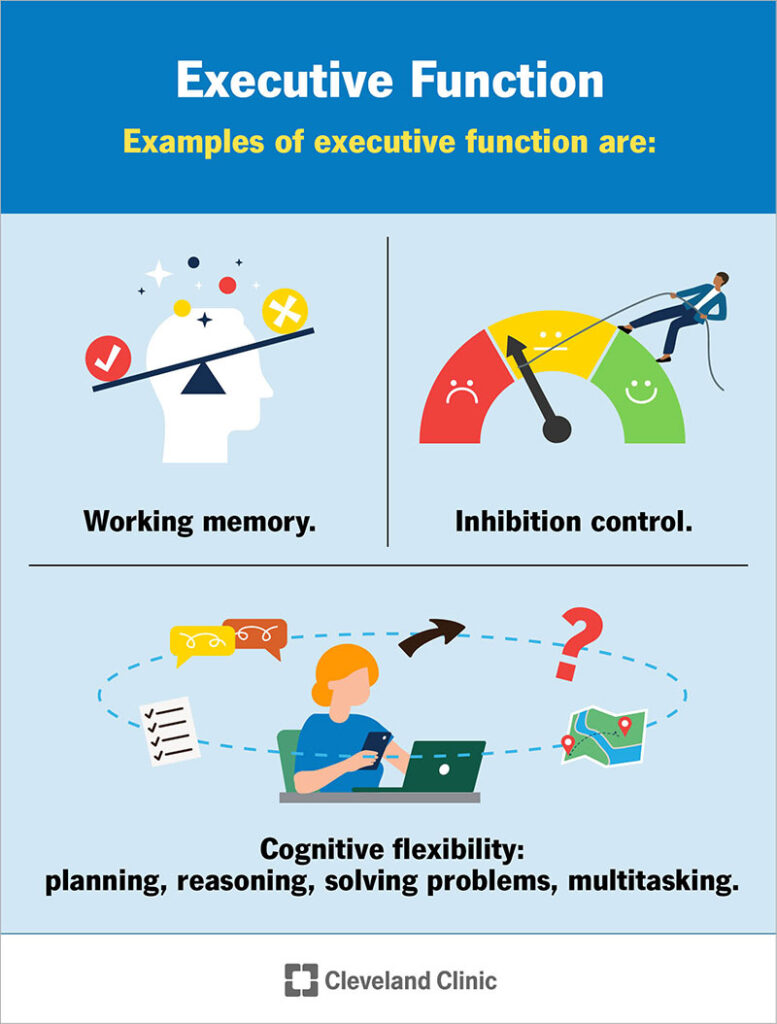

1). Executive functions are a set of skills processed in the prefrontal cortex that allow us to think, set goals, plan, organize, and follow through to achieve those goals. The three main functions that are considered to be executive functions are impulse or inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility.

Impulse or inhibitory control is self-regulation, controlling attention and focus, choosing how to act and not being at the mercy of our emotions. And how do we build impulse control while practicing?

We are practicing impulse control when we decide to practice rather than go to a movie; when we focus on working on a small problem area instead of just playing through the piece over and over; when we learn to concentrate and not be distracted in practice or performance; when we control our emotions rather than grimacing if something goes wrong in performance.

Working memory is what allows us to hold information in mind long enough to work with it or use it. There are two kinds of working memory: verbal and visual. You use verbal working memory when you remember the beginning of this blog post long enough to make sense of the end. You use visual working memory when you look at a map and hold the image in your mind while you drive so that you can find your destination (although with GPS, we don’t tend to use that particular form of visual working memory very often).

We use working memory constantly when we sight read. Whether we are consciously aware of it or not, we’re always looking a short distance ahead, our minds making calculations as to whether we will need to leave a note out of a chord in order to play it, how to keep a rhythm or melody going if we can’t reach everything, what fingering will work. We use working memory when we keep different interpretations in mind until we decide which we would like to use.

Cognitive flexibility is the ability to adjust our thinking or behavior in response to a changing situation. Trying different fingerings, different interpretations, different tempi are all examples of cognitive flexibility. Bouncing back in performance if something happens is also cognitive flexibility, as is quickly adjusting to a change in tempo indicated by a conductor.

2). Processing speed is a second cognitive function that declines with age, but not so much in musicians. Processing speed is how quickly our brain takes in, interprets, and responds to information. As we learn to play a musical instrument, we are integrating information that our eyes see in the score with the motor movements necessary to make those sounds, and our auditory system monitors the sound to see if we are playing correct notes. As we practice, we learn to sight-read and play more quickly, and our brain is learning to process all of this information at a faster and faster rate. As an advanced musician, we can react far more quickly to a mistake than we would as a student. Cognitive flexibility, an executive function, allows us to adjust to new information, such as a change in tempo. But processing speed is how quickly we are able to do so.

3). Hearing speech in noise refers, not to hearing, but to how well our brain processes sound. Both music and speech rely on the acoustical elements of pitch, timing, and timbre. Because music involves a far greater range of pitch than speech, far more complicated timing issues, and because musicians are accustomed to listening to the different timbres of different instruments, our auditory systems become more “finely tuned” than those of the general population.

Because we have lots of practice picking one voice out of many, hearing our own part within the harmony, hearing the melody even if it is in an inner voice, our auditory system becomes more accustomed to picking out the important part of a soundscape, so musicians are better at hearing “speech in noise.”

4). The fourth cognitive function that declines with age is visuospatial abilities such as depth perception, navigation, or coordinating movement with visual information. Playing an instrument requires sensory-motor coordination, quickly translating visual information in a score to physical motor movements that happen in space – at the same time monitoring the auditory feedback to see if what you are playing is correct. Musicians learn to think in time and space, even if we don’t consciously think about it in those terms.

As a child, you start out with relatively small movements and jumps, although even an octave jump at the keyboard can be a challenge for a child. But as you become more advanced, you play music with greater challenges (think of the end of the second movement of the Schumann Fantasie, with its nearly 100 large leaps.). Learning to equate visual space you see on the page with auditory space that you hear with kinesthetic space that you feel builds visuospatial cognitive reserve.

So when we are practicing a musical instrument, we are building cognitive reserve in the brain areas that process executive function, hearing speech in noise, and visuospatial abilities, and because we learn to do this more quickly over time, our processing speed improves as well.

Implications for an aging population

Here in the US, we have an aging population that is getting larger, and many other countries are experiencing that as well. Researchers and medical health professionals say there is a need for knowledge about the kinds of activities that will maintain brain health in older adulthood. The challenge in the field of aging is to develop training programs that stimulate neuroplasticity and delay or reverse symptoms of cognitive decline. To be successful, such a program should be easily integrated into daily life, enjoyable, and motivating.

And piano lessons fit the bill. A significant amount of research suggests that because making music places a demand on a number of brain networks involving multisensory and motor integration, the reward system, memory, emotion, and cognitive networks, it’s an ideal vehicle for preventing cognitive decline.

In the next post

Until very recently, the bulk of the research concerning cognitive functions and music has been conducted with children. In the next post, we will look at a recent comprehensive study done in Germany and Switzerland demonstrating that people in their 60s and 70s, who had never had music lessons, showed neuroplasticity, or brain changes, in these same cognitive areas, thereby building cognitive reserve, after just a year of piano lessons.

Delaying the aging process may not have been a reason your mother gave when she urged you to practice, but practicing may do exactly that – at least it keeps our brains healthier.

4 responses to “Music making as a “fountain of youth,” part 3”

Thank you. I have played the Oboe 62 yrs! Omg! I am only slightly slower and my eyes are not a teenagers eyes everything works great. And for me now living alone the social connections are paramount!! Make music and enjoy!! Peace to all!

Thanks, Dorothy! I hope you continue to play for many more years!

Great piece Lois! You are a true champion of helping us understand how we make music and how music makes us. I had to smile at your point about how little we memorize travel directions nowadays in our GPS-guided world; in his most recent book “I Heard There Was a Secret Chord”, Daniel Levitin makes the point that following directions by memory is a great exercise to help build working memory.

Thanks, Don! It didn’t take very many years for most of us to totally rely on GPS, although my husband still likes to use maps!