It’s long past time to get to the fourth and final installment of the series about “making music as a fountain of youth.” So here we are. This series has been stretched out over several months, so you may want to go back to reread the first and third posts. But to give a short recap: In the first of these posts, we talked about the cognitive functions that normally decline with age and how research has shown that musicians are stronger in all of these areas of cognition than non-musicians. When we study a musical instrument, we build cognitive reserve.

The second post in the series discussed activities other than making music that build cognitive reserve. In the third post we looked at the brain areas necessary for making music, and at how the process of making music strengthens the areas that contribute to cognitive reserve, as demonstrated by many studies with children. And that brings us to this post, which talks about a study that proved conclusively that listening to music and practicing a musical instrument promotes brain plasticity and cognitive reserve even in 60 and 70 year old adults who have never previously had any kind of music lessons.

The industrialized world has an aging population, and because of that, researchers and medical health professionals say there is a need for the kinds of activities that will maintain brain health in older adulthood. A significant amount of data has existed for some time that demonstrates changes in cognitive areas (neuroplasticity) in children’s brains when they study music. Over the past few years, there have been a few small studies involving adults.

An increasing number of researchers have suggested that musical practice is an ideal vehicle for preventing age-related cognitive decline because it places a demand on so many networks in the brain: sensorimotor areas, memory, emotion, the reward system, and cognitive networks. Learning a musical instrument also involves a gradual increase in difficulty, so there is a constant challenge. And making music is enjoyable. Neuroplasticity has been shown to occur more readily when you enjoy an activity.

The researchers

So a large group of researchers in Hannover, Germany and Geneva, Switzerland, designed a long-range, large-scale study to look in a more comprehensive way at the changes in the brain in elderly individuals that occur as a result of studying a musical instrument. These researchers represented the fields of neuroscience, cognitive psychology, cognitive neuroscience, neurophysiology, music medicine, neurophysiology of aging, auditory neuroscience, and more.

Geneva Musical Minds Laboratory

The two lead investigators were also musicians. Clara James is the director of the Musical Minds Lab at the University of Geneva, Switzerland and had a career as a professional violinist before getting a PhD in neuroscience.

Eckart Altenmüller, former head of the Institute of Music Physiology and Musicians’ Medicine at the University of Hannover (now retired), has also maintained an active performing life as a flutist. Many of you are familiar with Altenmüller’s name because he has done so much work in the field of musician’s medicine. In particular, he has been instrumental in discovering the causes of, and successful treatments for focal dystonia, a movement disorder that has affected so many musicians, including Leon Fleisher and Gary Graffman.

How the Study was designed

The study was designed to last a year, with post-study follow-up. They recruited 155 retired, healthy adults between the ages of 64 – 78 (63 in Geneva, 92 in Hannover), none of whom had had more than 6 months of any formal music training. (Interestingly, over 500 people applied to take part in the study.) Each participant was randomly assigned to either a piano playing group (the experimental group) or a musical culture group (the control group – a kind of music appreciation class).

Both groups had weekly 60-minute sessions for a year. The participants studying piano met in groups of two with a teacher, the musical culture groups had 4 – 7 participants plus teacher. Teachers were recruited from local universities, most were musical performance majors, all had at least a bachelor’s degree and were supervised by university professors.

The participants were tested at four times: baseline, at 6 months, 12 months, and at 18 months (6 months after conclusion of the training). They were tested on cognitive, perceptual, and sensorimotor abilities by a battery of tests. They also underwent MRI imaging and blood sampling.

Participants in the Musical Culture classes studied music from the Medieval to Contemporary periods in a variety of genres – orchestral, chamber, opera. They also learned about world music, jazz, funk, rock, and they learned how to listen to music analytically. The course materials were excerpts from textbooks, internet documentaries, radio broadcasts, TED talks, You Tube videos, etc. The participants were expected to spend 30 minutes a day on homework – listening, reading, and preparing 10 minute presentations, which they presented regularly to the class on topics of their choice.

Participants in the Piano Playing group each received a Yamaha P-45 B electronic piano, adjustable bench and headphones to take home for the duration of the study (as shown in the photo at the top of the page). These keyboards were supplied by Yamaha Germany and Switzerland, although Yamaha had no role in the study, which was funded by the German Research Foundation and the Swiss National Science Foundation.

The first three piano sessions were standardized, after that each group of 2 moved at their own pace. Among the materials used were two that are familiar to American teachers: Hal Leonard’s “Adult Piano Method,” and Edna Mae Burnam’s “A Dozen a Day.” Piano students were expected to practice 30 minutes a day, and were evaluated on technique, rhythm, expressivity, music reading, motivation, homework, and general progress. At various time periods (3 mo, 12 mo, 18 mo.) they recorded a simplified version of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.”

What did the researchers find?

1) In as short a period as 6 months, there was an increase in gray matter volume in both groups in an area of the frontal cortex having to do with executive functions. You can refer to the previous post to read more about executive functions but they are the set of skills that allows us to think about what we want to accomplish, set goals, organize our practice or study, pay attention to details, and follow through, all things we need to do as we practice or study.

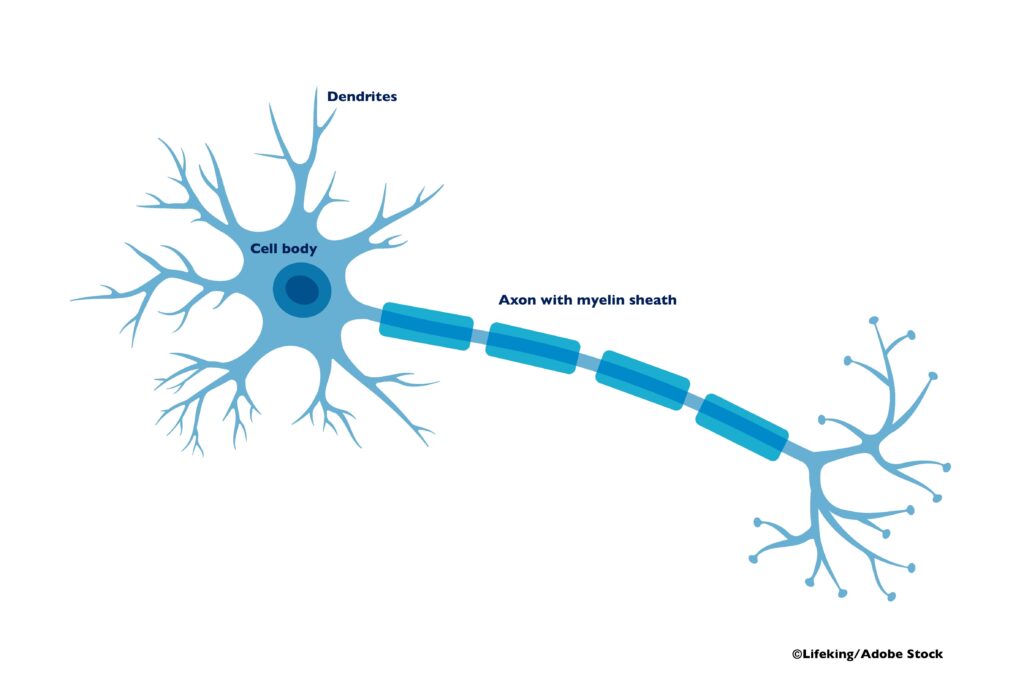

Gray matter refers to the cell body of the brain neuron where information is processed. In the image below, you can see the dendrites, which bring information to the cell, the cell body where it is processed, and then sent via the axon to connect with dendrites of another neuron, eventually forming a pathway or network of multiple neurons.

The increase in gray matter means that more neurons were being recruited to the task of either practicing (the piano playing group) or learning the study material ( the musical culture group). This increase in gray matter is neuroplasticity, which had been confirmed in multiple earlier studies with children learning to play the piano. But neuroplasticity was previously unheard of in elderly brains. So this study confirmed that neuroplasticity continues even as we age. And neuroplasticity leads to cognitive reserve.

2) White matter stabilized in the piano playing group in an area of the brain having to do with episodic memory, the memory for remembering events and when they occurred. Episodic memory is what gives you your sense of self and it is what is lost when people suffer from dementia.

White matter refers to the covering (myelin) on the axon, a projection from a neuron that connects to, and carries information to another neuron. The more you practice, the more white matter, or myelin, accumulates on the axon, stabilizing it. White matter tends to degrade as we age, causing slower cognitive processing. But practicing an instrument leads to stabilizing the white matter so it doesn’t degrade in a part of the brain having to do with memory, maintaining our episodic memory – cognitive reserve.

3) Hearing speech in noise improved in both groups, but there was more improvement in the piano playing group. As I mentioned in the previous post, hearing speech in noise doesn’t refer to how well we hear, but to how well our brain processes sound. Because we listen to multiple voices as we play the piano, as we listen to our pitch if we play a string, wind, or brass instrument, as we listen to see if we have played the right pitch and rhythm, as we listen to how our part fits into the whole if we are playing in an ensemble, our auditory system becomes more finely tuned – again building cognitive reserve.

4) At 12 months, both groups had improved in cognitive flexibility (see previous post) but there was slightly greater improvement in the piano playing group.

5) Also at 12 months, there were wide changes in functional connectivity in the piano playing group. Functional connectivity refers to how different parts of the brain collaborate even if they are not physically connected. Many areas of the brain are involved in playing a musical instrument, and they have to cooperate together. Sometimes they are physically connected by neuron networks, sometimes not.

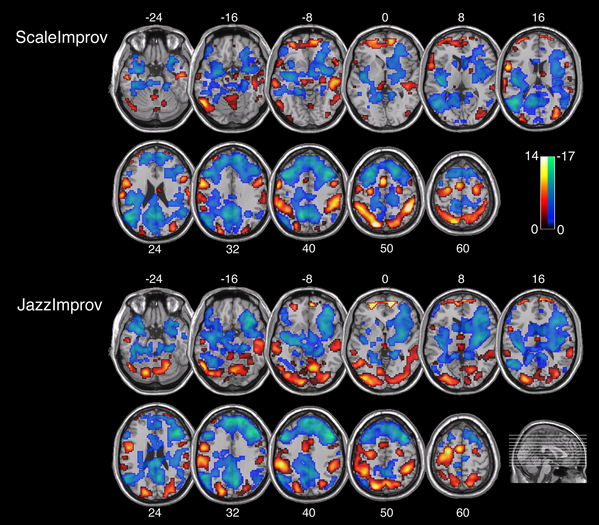

For example, the image below is an fMRI scan of a jazz musician improvising. This scan is not from the study we are discussing, but from a 2008 study of jazz musicians. The scan shows the areas of the brain that are active (red) and those that deactivate (blue) when playing jazz. In order to improvise, the areas of the brain that have to do with self-monitoring and inhibition must deactivate (blue). We can’t be constantly judging what we do when we improvise, we have to just let it flow. During improvisation, the areas that have to do with self-expression and creativity (red) are activated. How well these various areas of the brain work together when they are not connected structurally, activating and deactivating as needed, is called functional connectivity, and that improved over 12 months in the piano playing group – again building cognitive reserve.

Neural Substrates of Spontaneous Musical Performance

6) And in a follow-up at 48 months, the researchers found that the piano playing group, many of whom had continued studying the piano, reported an improvement in their quality of life. The researchers suggest that, from a public health perspective, music courses could be a good approach to promote healthy aging and improve quality of life.

conclusions

There are at least a dozen papers published in various research journals concerning different aspects of this study. The protocol for the study is open access and I have linked to it below in case you would like to read more.

There was a tremendous amount of material to cover with this study, so if any of it isn’t clear, please e-mail me with any questions using the contact link at the top of the blog post.

This study proves rather conclusively that neuroplasticity is still possible in the older adult brain, and that music lessons, at any age, build cognitive reserve and are therefore good for brain health. And in addition, music lessons contribute to quality of life. As musicians or lovers of music, we already know that music contributes to our quality of life. But how wonderful to find out that it also contributes to healthy aging. What could be better than that?

Leave a Reply