And a few more practice strategies to ensure effective learning and memory:

5) Practice extremely slowly. There has been a controversy for some time about whether slow practice is beneficial for learning fast music. Many of us were told early in our musical lives that in order to play a passage of music that is very fast, we should practice slowly and build up speed. But not everyone agrees. Influential pedagogue Abby Whiteside (1881 – 1956) declared that “Slow practice can establish habits that are completely unrelated to the coordination demanded for speed.” Abby Whiteside on Piano Playing

5) Practice extremely slowly. There has been a controversy for some time about whether slow practice is beneficial for learning fast music. Many of us were told early in our musical lives that in order to play a passage of music that is very fast, we should practice slowly and build up speed. But not everyone agrees. Influential pedagogue Abby Whiteside (1881 – 1956) declared that “Slow practice can establish habits that are completely unrelated to the coordination demanded for speed.” Abby Whiteside on Piano Playing

And neuroscientist Eckart Altenmüller says essentially the same thing concerning slow practice. In The Science and Psychology of Music Performance (2002), Altenmüller suggests that different brain areas are responsible for slow and fast movements: slow movements are “under steady sensory control,” and fast movements “have to be performed without on-line sensory feedback,” meaning we can’t monitor the notes as fast as we play them (p. 76-77). So practicing at a slow tempo may hamper playing the passage at a fast tempo.

areas are responsible for slow and fast movements: slow movements are “under steady sensory control,” and fast movements “have to be performed without on-line sensory feedback,” meaning we can’t monitor the notes as fast as we play them (p. 76-77). So practicing at a slow tempo may hamper playing the passage at a fast tempo.

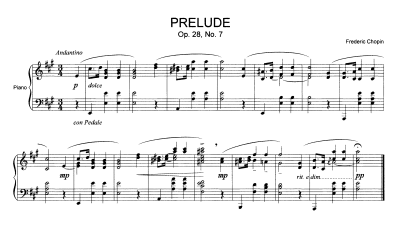

But that distinction has to do with motor skills. Slow practice can be extremely helpful in terms of solidifying long-term memory. Let’s return to the example in the previous post of the Chopin Prelude in A major. If we were to practice this Prelude at sixteenth note = M.M. 60 or even

slower (yes, sixteenth notes ), the very slow speed forces us to think about what comes next. There is no way we can play anything on automatic pilot.

slower (yes, sixteenth notes ), the very slow speed forces us to think about what comes next. There is no way we can play anything on automatic pilot.

We have to think about every single note, chord, rhythm, articulation, phrasing, etc. If we aren’t sure, for example, how the second statement of the theme is different from the first, then we have to specifically note that the R.H. ties over the E and adds a G# in the second statement. That we are noting the difference means the brain is making that distinction and encoding it. The neural pathways become more securely consolidated.

The jury may still be out on whether or not slow practice is good for developing fast motor skills, but there is no doubt that extremely slow practice is beneficial for reinforcing learning and memory.

6) Practicing in more than one venue on a variety of instruments adds different contextual cues to our encoding of the musical material. (See previous post for more on context.) Pianists are at a disadvantage when it comes to performance because we don’t carry our own instrument with us, as do most other performers. Each time we play in a different venue we have to become accustomed to a new instrument, so we always like to practice on the instrument on which we will perform and in the venue where the performance will take place.

We like to know how the piano sounds in the hall, what the problems are with the instrument, how the pedal responds, what works well and what doesn’t, how resonant the acoustics are. We like to imagine ourselves in that venue so we will feel comfortable when it’s actually time for the performance. And while other instrumentalists and singers bring their own instrument to the performance and don’t have to adjust to a different one, they still want to know how their instrument sounds in the hall, what the acoustics are like, how it feels to perform in that space.

So practicing on the instrument on which you will perform is important. But to ensure solid learning and memory, it’s also important to practice in different environments on different instruments – to change the context in which we practice. In a study done in the mid-1970s at the University of Michigan, three psychologists – Steven Smith, Robert Bjork, and Arthur Glenberg, performed an experiment* to find out if changing venue when one studied could add recall of information.

Two groups of students studied a list of forty words in two 10-minute sessions that were a few hours apart. The first group had both study sessions in a small, cluttered, windowless basement room. The second group did their first study session in the basement room, but the second in a comfortable room with windows overlooking a courtyard.

Three hours later, the researchers asked both groups of students to write down as many words in ten minutes as they could remember from their previous study sessions. This time they were in a classroom, quite different from either of the study session rooms.

The researchers found that the second group, which had studied in two different environments, was able to recall more words by a factor of 40% – which is rather significant. The researchers suggested that the brain may encode some words in one environment, and different words in a second environment. Or perhaps studying in two different environments means attaching more contextual cues that are linked to a word – or to a section of music.

Just to clarify, there are studies that show that we recall information better when we are asked to recall the information in the same place in which we learned it. Had the first group done the recall part of the experiment in the same room in which they had both study sessions, they would probably have done very well. But the test was in a different room, just as we almost always perform in a venue different from our practice space. In that situation, having practiced in more than one space adds contextual information that helps recall.

When we are in our usual practice space, we tend to concentrate on technical issues, memory, interpretation, and all of that is encoded in the context of that space. When we enter the hall, we are suddenly confronted with different acoustics and a different instrument (if you’re a pianist.) The piano action will respond differently, we may have to voice in a different way, we have to think about projection, about pedaling, so we are thinking about different issues with the music in the context of a different space and adding that information to what we already know about the piece. We are adding more contextual cues to the neural circuitry that already exists for that piece.

This isn’t a conscious process; contextual information is always added when information is encoded in the brain. That’s why smells sometimes trigger memories, because the smell has been encoded along with the memory. So obviously, the more venues we have practiced in, and the more instruments we have played, the more contextual cues we have – which aids recall.

To be continued.

* Steven M. Smith, Arthur Glenberg, and Robert A. Bjork. “Environmental Context and Human Memory,” Memory & Cognition, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1978, 342-53.