Lascaux Cave

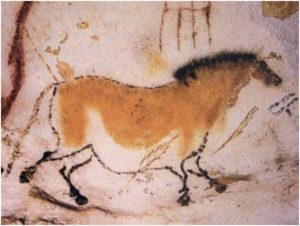

A few weeks ago, my husband and I visited Lascaux Cave, a well-known Paleolithic cave in southwestern France. Many of you have seen illustrations like the one below – one of about 600 cave paintings at Lascaux with another 1400 or so engravings dating to somewhere between 17,000 and 15,000 BCE.

Actually one cannot enter the real Lascaux Cave, which was designated as a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1979. Discovered in 1940, it was opened to the public in 1948, but the 1200 visitors/day produced carbon dioxide, heat, humidity and contaminants that began to visibly damage the paintings. So it was closed to the public in 1963. The only people now allowed in the original cave are technicians/scientists who monitor the preservation of the site.

One can visit Lascaux II, opened in 1983, an exact replica of three of the halls of the cave. Or you can choose Lascaux IV, a high-tech digital, multimedia site that opened in 2016. We chose Lascaux II – wanting a more “authentic” experience.

The paintings are far more spectacular than one can imagine from seeing illustrations. Pablo Picasso, probably the most influential artist of the first half of the 20th century, visited Lascaux in 1948 shortly after it opened and expressed amazement at the quality of the rock art. He was reported to have said that man had not learned anything new since then.

And our guide, who was an archaeologist, continually pointed out features that indicated these primitive painters were quite advanced, as Picasso indicated. They demonstrated an ability to show motion, a kind of perspective in the way the hind legs of bison are crossed, a way of using the natural contours of the walls to create depth, an ability to mix pigments for the paintings, a knowledge of how to erect scaffolding because the paintings are very high in the caves – sometimes on the ceiling, and even an ability to depict an eye of a bull in one painting so that it seems to follow you wherever you are in the cave chamber. In fact archaeologists say, in order for cave art and the bone flutes discussed in the previous post to be so sophisticated by 40,000 years ago, they must have evolved from even earlier artistic traditions.

When I asked our guide over lunch about research I had read concerning acoustical “hot spots” in these painted caves suggesting a connection with music, he said “Absolutely. Music, art, and ritual were all connected.”

So what did cave paintings have to do with music and ritual?

Painted caves

Although France and Spain are particularly rich in cave sites with paintings (340 caves), Paleolithic caves with paintings or engravings on walls and ceilings have been found on every continent except Antarctica. These paintings range from dots and abstract patterns to tracings of human hands to images of animals such as bison, horses, aurochs, and mammoths.

Not incidentally, fragments of bone flutes, bullroarers, and small figurines have been found in or near some of these Paleolithic caves. As I wrote in How Old is Music?, archaeologists believe these musical instruments and figurines point to a religious or ritualistic purpose within the cave.

And archaeologists consider the caves themselves to be a musical instrument. A cave is a kind of giant resonator, amplifying everything from footsteps, voices, and dripping water, to the sound of an underground river running through the cave system. Stalactites and stalagmites may ring like giant tubular bells when struck. Acoustics in a cave vary a great deal depending on size of the space, but also on whether the floor, walls, and ceiling are made of hard stone, softer stone, or perhaps clay.

Over the past thirty plus years, studies have shown there is a relationship between the cave paintings and the acoustics of the area of the cave where they are found. Archaeologists believe this relationship points to a ritualistic purpose for the painted caves just as for the ivory and bone flutes that have been found in or near them.

Cave paintings and music

Iégor Reznikoff, University of Paris, is a classical pianist with a PhD in mathematics who describes himself as a specialist in the resonance of buildings and spaces, but he has primarily been associated with the resonance of Romanesque churches. He is also a pioneer in the field of archaeoacoustics (sound archaeology). He reportedly sings or hums to himself whenever he enters a new space to learn about the resonance in all portions of the space.

So the first time he visited a cave with cave art in France in 1983, he sang and hummed in different parts of the cave to test the resonance, which is what he was used to doing in churches. He discovered that his humming was louder and more resonant when he was in rooms with painted animals like bison and horses, so he wondered if there might be a connection between the amount of resonance and the locations of the paintings in a cave.

To test his idea, Reznikoff visited more than ten painted caves in France with art ranging from 15,000 to 25,000 years old, singing as he explored the caves. He outlines his conclusions in Sound resonance in prehistoric times: A study of Paleolithic painted caves and rocks. But basically:

- Most of the paintings (up to 90%) were located in the most resonant locations of a cave, where echoes would reverberate for some time.

- The more resonance, the denser the paintings.

- In areas such as narrow passageways where painting would have been difficult but the acoustics were still good, there were often markings of red dots.

More recent studies confirm his findings. In 2013, Rupert Till, an acoustic archaeologist at the University of Huddersfield, UK, and a group of researchers explored five of the Catabrian Caves in Spain. Using more modern techniques than were available when Reznikoff did his initial studies, Till and his team recorded data at many locations in these caves, collecting specific information about acoustics including the distance from the sound source to the painted motifs, giving them an acoustic fingerprint of each chamber or tunnel in the caves. They also collected data about how many of each kind there were of engravings, dots, handprints, and paintings of horses, bison, mammoth, and other animals, as well as colors used in the paintings and the distance of the paintings from the cave entrance.

https://www.exploringcantabria.com/en/news/experiencias/caves-in-cantabria/41

They found that the older paintings (up to 40,000 years old) are in smaller, less acoustically resonant spaces and include simple things like dots or handprints. Paintings from 15,000 to 25,000 years ago tend to be paintings of animals such as deer, bison, horses, and mammoths, and they appear in much larger, more resonant spaces – large enough for groups of people to have rituals – caves such as Lascuax.

Both Reznikoff and Till believe the correlation of paintings and resonance points to a ritualistic or religious reason for the paintings and Reznikoff asks: Why would the Paleolithic tribes choose preferable resonant locations for painting if it were not for making sounds and singing in some kind of ritual celebrations related with the pictures?

Archaeologists speculate that the rituals, since they involve animal paintings, celebrated the number of animals killed during a hunt, or they may have preceded the hunt and were a kind of ritual to ensure success. So we can imagine groups of early humans playing the flute, perhaps singing and dancing, in large chambers in caves where the acoustics would have been particularly resonant.

And what about singing?

While the earliest instruments found date to around 40,000 BC (although there is some evidence of earlier instruments), the primary musical instrument is the voice, and use of the voice for vocalization dates back far earlier. Researchers suggest that the human voice gained its full vocal range at least 500,000 years ago. Certainly by the Paleolithic era, early humans had vocal and auditory capacities that are similar to our own.

And they no doubt sang during rituals in the acoustically resonant caves. But the voice is a remarkable instrument, and early humans didn’t just use it for artistic reasons. The voice also had a purpose in exploration of the caves for safety.

The voice and echolocation

We know that dolphins and bats use echolocation, or biological sonar, to locate and identify objects that may be close to them. Humans can also be trained to do this, tapping canes or making clicking noises to gauge information about the environment by listening to the echoes from the clicks or tapping to identify nearby objects.

Archaeologists suggest that early humans had the ability to use echolocation and, not only did they use it to find the most resonant areas of the caves for paintings, they also used it to explore caves to determine size of areas they were entering and to determine which areas were safe and which were not.

Caves are extremely dark. These early painters would not have had anything other than candles or some kind of oil lamp with which to see. But sound carries further than light, and they could explore the caves using their voices. The echoes coming back to them as they sang or vocalized throughout the cave would tell them which were the most resonant halls for painting. But those echoes also alerted them to danger if, for example, as they were moving forward through a cave, they began hearing the echoes coming from below, indicating a hole in the cave floor, and an even deeper subterranean cave.

Reznikoff has been known to locate paintings in dark caves simply by using his voice to find the most resonant areas, and the paintings will be there. On the site Songs of the Caves, there are two clips from a BBC production in which Reznikoff demonstrates various kinds of sounds in caves.

As you listen to the two clips demonstrating how caves may have sounded to our prehistoric ancestors, think about how old music really is and how long it has been an integral part of people’s lives.

6 responses to “Music and prehistoric cave art”

In History of Art H.W. Janson says that there is evidence that the big herds withdrew northwards when the climate of Central Europe grew warmer. He thinks that at Lascaux and Altimira the ritual magic may have not been to “kill” but to “make” animals — increase their supply. That is how he speculates about the extraordinary realism of the cave art and that the art is created in caves — the womb of the earth.

Very interesting, Roz! Thanks so much for sharing Janson’s ideas!

Sounds great….I would love to see it, even the re-created version.

Hi Steven, You really do feel as though you are in the real cave, except for the floor, which our guide said was 3 meters higher than the original. We had to crane our necks to see some of the art in spite of the raised floor, so in the original, the artists really needed some serious scaffolding.

A wonderful post, Lois. The cave-shape makes me think of the shape of a church or other similar places of worship as kinds of “caves of god”. Obviously the churches also produce similar effects: echoes for music, echoes empowering the priest’s speech, and certainly also feeling of a shelter for the group of people inside. And they, too, are filled with art. So there must exist a general need of the humans to create (or occupy) spaces where they can be surrounded by sounds and pictures.

Great to hear from you, Paavali! The church-cave connection is interesting, and it’s probably not surprising that Iégor Reznikoff, the specialist in the acoustics of Romanesque churches, has also become a specialist in the acoustics of caves. And I think you’re right that there is a need for humans (and has been for tens of thousands of years) to surround themselves with music and art. And on another note, we’re looking forward to your performances in the States in the fall.