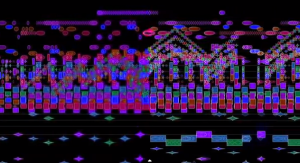

This wonderful image is not your brain on music. It’s from Stephen Malinowski’s animated graphical score of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps: Part I and Part II. A few months ago, at the time I was thinking about starting this blog, a lot of media attention was being directed to the 100th anniversary of the famous, riot-inciting premiere of The Rite of Spring (May 29, 1913). I discovered Malinowski’s video on PostClassic, Kyle Gann’s comprehensive, informative and thought-provoking blog about new music. (If you aren’t already familiar with Kyle’s blog, you should check it out.)

This wonderful image is not your brain on music. It’s from Stephen Malinowski’s animated graphical score of Igor Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps: Part I and Part II. A few months ago, at the time I was thinking about starting this blog, a lot of media attention was being directed to the 100th anniversary of the famous, riot-inciting premiere of The Rite of Spring (May 29, 1913). I discovered Malinowski’s video on PostClassic, Kyle Gann’s comprehensive, informative and thought-provoking blog about new music. (If you aren’t already familiar with Kyle’s blog, you should check it out.)

I’ve heard Le Sacre dozens of times, performed Stravinsky’s four-hand version multiple times, seen both the Joffrey Ballet’s recreation of the original and other ballet versions, and taught the historical and musical implications in music history classes. I’d say that I know the piece pretty well. But as I watched Malinowski’s animated score unfold, I was struck by the fact that I was hearing very familiar melodic and rhythmic patterns in a totally new way – even hearing some things I seemed to have not noticed before – because I was seeing the musical patterns revealed in colors and shapes.

Patterns. According to neuroscientist Paul Bach-y-Rita (1934 – 2006), all sensory information, whether from eyes, ears, nose, tongue, or skin, enters the brain as patterns, and so is in some way equivalent. He often said that “we see with our brains, not with our eyes.” Light entering the eye is converted by cells on the retina into electrochemical signals – patterns – that are sent to the visual cortex via the optic nerve and processed as images (a musical score, for example). The sounds we make on our instruments or with our vocal cords enter our ears as sound waves and are turned into neural impulses – patterns – in the inner ear, then sent to the auditory cortex for processing. So we also hear with our brain, not with our ears.

In the late 1960s Bach-y-Rita introduced the idea of sensory substitution – stimulating one sense to take the place of another. He built a device called the Brain Port, which in one application, serves as a person’s eyes by sending visual information from a head-mounted camera to electrodes on the tongue. The visual information, after being turned into electrical impulses by a computer, is felt by the tongue as vibrations. The brain translates the pattern of the vibrations from the tongue into information for the user about size, location, and shapes of objects that the camera is “seeing.” The non-sighted person isn’t seeing visual images in the same way a sighted person would, but the brain is turning touch patterns into rudimentary visual information that helps the non-sighted person navigate his world more easily.

Are Malinowski’s visual patterns and Stravinsky’s auditory patterns equivalent in the brain? We don’t know, since, to my knowledge, no one has compared visual and auditory sensory input for a specific piece of music. But whether or not the auditory and visual patterns have some kind of equivalency in the brain, seeing the patterns while hearing them enhances the learning process. Study after study shows that information is solidified in the brain and you increase your ability to recall the information if it has been encoded in more than one way. We all know that if you are learning a foreign language, visually studying a text won’t take you very far. You need to hear and speak the language. And if you actually experience living in the country where that language is spoken and you eat the food, go shopping and interact with people, your proficiency will increase dramatically because your brain has encoded information about that language in multiple ways.

Most of us have experienced a teacher who urged us to visualize the music, to move to the music or to make up stories about the music. I’ve encouraged my students to approach music with different senses, and I’ve done the same. But I was still fascinated to discover how much the auditory patterns in Le Sacre – temporal, harmonic, and melodic – were reinforced and made more apparent by seeing Malinowski’s computer-generated visual patterns of repeating colors, shapes, and directions. I know the score and can visualize the notation, but seeing the music in shapes and colors gave me a different way of hearing the piece. (This of course, leads us to contemplate synesthesia, but we’ll talk about that another time.)

As musicians, we work with patterns all the time. We see patterns in the notation, and the ability to see those patterns helps us to be better sight-readers and to learn the music more quickly. We hear rhythmic, melodic and harmonic patterns, and the better we are able to hear and recognize those patterns, the easier it is to memorize. As you listen to and watch Malinowski’s version of Le Sacre, see what effect the visual patterns have on the way you hear the music – or vice versa. Then the next time you learn a piece of music (or even listen to a piece that you like), draw visual patterns – on paper or digitally – that represent the music to you. See how much faster you learn it by feeding your brain both auditory and visual patterns. And you may want to check out Rebecca Payne Shockley’s Mapping Music, published by A-R Editions. Becky shows you how to create and use a mental map to form your own visual blueprint of a score. And coming soon: a website by Melissa Colgin about Becky and Melissa’s mapping work. I’ll direct you to the site once it’s online.

******

If you’ve read this far and want to leave a comment, please be aware that the “Leave a reply” at the bottom of the page is intended for comments you wish to be public on the blog. If you’d like to contact me privately, use “Contact” in the menu bar. Thanks!

6 responses to “Patterns in the Brain”

My 1st Lois blog entry! I’m so happy you are doing this. Fantastic subject and I love your writing. Can’t wait for more.

Thanks Nancy!

This was absolutely mesmerizing.

So glad our many lunch-time conversations are being shared with the internet world. The subject of patterns is one of my favorites – well done!

Seeing patterns in, and the pattern (or gestalt) of, a piece helps me greatly, but the ability came only late in life, after years of what I in retrospect understand as having been too caught up in the details – the trees rather than the forest. It seems easier to have the overall pattern in my head and tweak the details rather than trying to tweak the details to get the overall pattern. I’m guessing personality type has a lot to do with how that works out for various individuals. My feeling is it’s one of those things you have to experience before the words of anyone trying to teach it will convey the deep meaning.

Patterns that don’t seem to be talked about as much are the physical gestures we use to make the music and those physical gestures suggested by the music (even embedded in it) than can convey a strong emotional substrate to the music.

My intuition suggests that in great music there’s a sort of fractal nature to the patterns, in that the smallest reflect, inform and reinforce the largest and visa versa.

Some students are able to see and hear musical patterns more easily than others, and a lot of students are caught up in the details, but learning to be aware of auditory and visual patterns can be taught. There is an Oxford publication, unfortunately no longer available unless you can find it used somewhere, called Help Yourself to Sight Reading by Daphne Sandercock. She teaches sight-reading with exercises that train the eye to see increasingly more complex visual patterns and calling attention to the sound of those patterns. As you say, physical gesture should be talked about – and interesting idea about fractals – I’ll have to give that some thought.