In my first post, I wrote that many neuroscientists believe that “making music is the most complex cognitive activity that a human being engages in.” Some readers wondered why, so let’s talk about it. After the research that’s been done in the past two or three decades, neuroscientists believe that the processing of music in the brain happens in multiple separate modules or neuronal networks – each processing some aspect of music, all working together to make it possible to listen to, and to perform, music. Imagine for the next few paragraphs that you are playing an instrument and let’s look at a very simplified version of what is happening in your brain.

First of all, you had to learn a second language – music notation – and that’s not an easy task. Never mind that notation shouldn’t be taught first when learning an instrument. It often is, and we’ll get into why it shouldn’t be another time. So as you look at the page of symbols, all of the visual areas of your brain become active, both to process the information entering the eye, and to turn it into what we perceive as notation. Even if you are improvising and not using a score, the visual areas of your brain are processing information that allows you to recognize your instrument, your hands, your surroundings, cues from other performers, etc.

Ideally, you match a symbol you see on the page to a sound that is produced by playing a particular key on the piano or by strumming a particular string on the guitar. That sound enters your ear as a sound wave, and all auditory areas of your brain are involved in processing that sound wave and turning it into what we recognize as a musical pitch.

So both the auditory and visual areas of your brain are now involved. But backing up a bit, before you can push the key or strum the string resulting in a pitch, your brain has to plan the appropriate movements to initiate the sound. So now all of the motor areas of your brain are involved, both the areas involved in planning the movement and the motor cortex itself, which sends the signal to your muscles to actually initiate the movement. The cerebellum is also involved in the timing and accuracy of motor commands, and researchers have found that the cerebellum helps musicians interpret rhythm.

In the majority of people, the left side of the brain controls the right side of the body, and the right side of the brain controls the left side of the body. No matter what instrument you play, you are usually using both hands, so here’s the cerebellum again, playing a critical role in coordination of your movements. Singers don’t need their hands to sing, but they are using a text, and text is primarily (not totally) processed in structures in the left hemisphere, while melody is primarily processed in the right hemisphere; so again, networks in different areas of the brain must coordinate.

Now we need to add the brain areas having to do with emotion, sight-reading, memorization, or recall of that memorized music when you are ready to perform. And, to add to the complexity, what is referred to as a local mode of cognitive processing (e.g., single intervals, single pitches, rhythmic motifs) occurs, to a large extent, in areas of the left hemisphere. Global processing (e.g., melody or meter) occurs largely in areas of the right hemisphere. (We’ll come back to those distinctions in another post.)

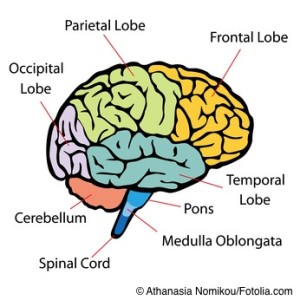

I can’t show you a beautiful fMRI image of a musician performing onstage that shows all of the areas of the brain that are active during performance. Most of you know how an MRI works and know that it could not be  used onstage during performance. But evidence about the multiple brain areas involved in performance has accumulated one study at a time studying one neuronal network at a time, generating images of one brain area at a time. So instead of an actual brain image, take a look at the attached drawing that shows the four lobes of the brain – temporal, frontal, parietal, and occipital. Some processing related to music occurs in all four of these lobes – in both the right and left hemispheres. In addition, processing for music happens in the cerebellum, as well as in internal parts of the brain that you can’t see in the image, such as the basal ganglia, the thalamus, and the amygdala. So a great deal of brain real estate is used when we are making music.

used onstage during performance. But evidence about the multiple brain areas involved in performance has accumulated one study at a time studying one neuronal network at a time, generating images of one brain area at a time. So instead of an actual brain image, take a look at the attached drawing that shows the four lobes of the brain – temporal, frontal, parietal, and occipital. Some processing related to music occurs in all four of these lobes – in both the right and left hemispheres. In addition, processing for music happens in the cerebellum, as well as in internal parts of the brain that you can’t see in the image, such as the basal ganglia, the thalamus, and the amygdala. So a great deal of brain real estate is used when we are making music.

Is it important to know what elements of music are being processed where in the brain? No – and yes. No, because we can’t think our way to using one part of the brain or another. If we actually had to think about all of the connections that must occur in the brain in order for us to make music, we would be so overwhelmed, we would never play a note again. But yes, it is important to know that the ability to perform music involves many areas of the brain because at least one study has shown that different ways of teaching music activate different parts of the brain, and that has implications for how we learn. More about that next week.

4 responses to “Most complex cognitive activity”

Very nice summary in non-technical language – thanks for putting it together – and really looking forward to the next post.

One thing to perhaps add to the list is the social aspect of performing (or imagining an audience while practicing). To some degree I think we see, hear or feel how an audience is responding to the music – and that gets factored into how we’re playing. Here’s a great quote from Hilary Hahn from years ago that gets at what I’m saying. My idea is that there must be some part of the brain dealing with this aspect of music making.

>>The problem is that acoustic performers rely on the audience’s attention and focus and can tell when the audience isn’t mentally present. Your listening is part of our interpretive process. If you’re not really listening, we’re not getting the feedback of energy from the hall, and then we might as well be practicing for a bunch of people peering in the window. It’s just not as interesting when the cycle of interpretation is broken.<<

Good point about the audience, but that still involves the areas of the brain that are processing visual, auditory, and emotional information. It’s just a widening of the performer’s focus to include more sensory input than just the music.

I suspect this is right – instrumental musicians may demonstrate the most complex brain activity when performing. But top level mathematicians must be close behind – and, of course, there are many correlates between music and math. As to what role the audience plays, it must vary. Why did Gould give up public performance? Just shyness, or something else? As to memory of the task, such applies to many people – though enjoying Paavali performing the entire 2 hours of Messeaen’s tribute to the Infant without a break was to witness a prodigious feat. For myself, performing a 3-4 hour operative procedure was different. There, I was deciding on a course of action, whether to change emphasis or not, every few moments – not the same thing at all, and I yield the floor.

There are obviously lots of activities that are cognitively very complex – brain surgery certainly being one of them. And neuroscientists study a lot of different populations to see what’s going on in the brain (I just read a study about spinning ballet dancers). But I think what captures the interest of neuroscientists with music is the extremely fast processing that coordinates virtually all of the senses (except smell) with motor movement. The sound you hear yourself generating in any fraction of a second gives the brain feedback about generating further movement to produce more sound – and it all happens nearly instantaneously. Gould gave up public performance because he was enamored with recording. He loved being able to play something more than once – and once said something to the effect of: “wouldn’t it be nice if, when something didn’t go well in concert, you could just say to the audience ‘I think I would like to try that again.’ Or if a passage was particularly beautiful, I’d like to say,’that was so beautiful – let’s hear it again.’” But even Gould wouldn’t do that in public performance, so gave it up, and just devoted himself to recording, where he could get things just the way he wanted. I’ve often wondered what kind of recordings he would make now – with current technology.